Editor’s note: Five years ago, we published one of my favorite stories, and I wanted to share it with you here.

Matthew Hua relished his first season of cross country at J.E.B. Stuart High School (now Justice High School). With no prior athletic background, his 24-minute three mile time is a point of pride. Lifelong health problems have been an obstacle in his running career, but they haven’t stopped him from fully participating as part of the team — except maybe in the team dinners.

Matthew’s gastrointestinal system has never functioned normally. He is unable to eat at all and drinks very little. In fact, virtually every one of his bodily systems is compromised. He is deaf in his left ear and his left vocal cord is paralyzed. Underdeveloped lungs have led to chronic conditions such as tracheomalacia (softened cartilage around the trachea) and asthma. He has ongoing orthopedic problems and his immune system is compromised, leaving him susceptible to infection and illness.

The Washington D.C. metropolitan region ranks near the top of most lists of things that cause stress — from traffic to cost of living, poverty, work demands and more. And since November, tensions have seemed to run higher than usual in the city, with the fate of federal jobs seemingly hanging in the balance. But you don’t have to buy a coloring book or move to Canada to feel better. Whatever your worries, locals in the know agree that running is a vital tool to care for yourself in stressful times.

Just ask Dr. Keith Kaufman, a runner and a clinical psychologist specializing in sport and exercise psychology. At his Northern Virginia practice, he works with high-performing athletes and beginners trying to develop exercise routines. He’s seen it all — student athletes pushing themselves to the breaking point, elites trying to achieve new heights in performance and of course the stereotypical Type-A D.C. professional whose day is scheduled down to the minute. A self-described Type A himself, Kaufman is an evangelist for running to manage stress or anxiety.

New School, New Team, New History

When Charles J. Colgan, Sr. High School opened last year, there were no championship banners hanging in the gymnasium. No trophies lined the trophy cases. No records existed to be broken by ambitious younger generations. Traditions, legends, the stuff of student mythology was yet to be written. So when administrators chose to field a varsity cross country program in the school’s first year, there was only potential before them.

They hired Dave Davis and Bill Stearns, two of the most accomplished coaches in local running, to build their team. Davis was a 2012 finalist for the Brooks Inspiring Coaches award and was inducted into the Virginia High School League Hall of Fame in 2011. He has won seven state titles to Stearns’s five. Stearns, for his part, has coached a Marine Corps Marathon winner, state and national champions, and All-Americans across his career. With Davis’s longtime assistant coach Melissa Tirone rounding out the leadership, they formed a kind of coaching dream team. Their task? Develop their athletes until they could challenge any of the other eleven schools in Prince William County.

Three years ago, we introduced the running community to Matthew Hua, a runner at J.E.B. Stuart High School who would not allow his unique medical condition slow him down. In the time since, Matthew has proven unstoppable. In fact, within four days, Matthew hosted a dinner for the many champions who’ve supported him and his family over the years, graduated from Stuart with an international baccalaureate diploma and underwent surgery to further improve his breathing capacity.

RunWashington caught up with Matthew and several of his champions to find out what has changed in his life since 2015, and how running has changed him.

Runners who enjoyed the mild start to May were reminded Wednesday morning that conditions can get uncomfortable and downright dangerous quickly. And more likely than not, tough temperature and humidity will be a factor for the next few months.

Nowhere was that more apparent than at the ACLI Capital Challenge in Anacostia Park, an annual three-mile race that gathers a collection of runners and non-runner colleagues, game for the competition, from the three branches of government and the media.

On Oct. 1, 2016, seven-year-old Lily Rancourt wore her Wonder Woman costume and brand new red sneakers with “hero” and “heart” on the tongues. With her family and friends, she braved cold and rain to toe the starting line for the Race for Every Child 5k in D.C.

At Lily’s urging, “We Don’t Miss a Beat” became the largest team at the race, and along the way, team members raised more than $18,000 for the Cardiology and Heart Fund at Children’s National Medical Center, making it one of the top fundraising teams, too.

The Rancourt family finished together in 1:04:48. Lily spent the entire race dashing ahead of her siblings, then waiting for them to catch up, offering encouragement.

Lily inspired and motivated an entire team to join her that gray October day and raised money for children to receive treatment for all types of cardiovascular problems. But Lily Rancourt isn’t just a big-hearted little girl. Behind the hero logo across Lily’s chest that day hid another heroic mark, a scar left when Lily received her own heart transplant one month before her fifth birthday. Since then, the first grader has regained her health and achieved her dream of running and playing with her siblings.

Taking Risks

Lily was born July 22, 2009 in inner Mongolia with a congenital heart defect. She lived in an orphanage and underwent two open-heart surgeries before doctors deemed her terminal and declined further treatment. She held on as family after family reviewed her adoption file and chose not to bring her home with them. She seemed like too big of a risk.

“I just could not get her off my heart. I kept feeling that if nobody goes for this little girl, then she’s going to die an orphan because they’re saying that she’s terminal and there’s nothing that could help her,” she remembered. Jacques hesitated. Four children, one of them critically ill, seemed overwhelming to a young family. Emily asked him to pray about it.

“I really think this is our daughter,” she told him.

After being adopted, Lily began a difficult course of medical exams and treatment. Doctors at Children’s National Medical Center found that Lily’s major organs were all mirrored from their usual positions in the body, complicating any surgeries. Her right pulmonary artery no longer pumped blood to her right lung. With one lung out of commission, the real danger came from a heart that was only half-formed and could not move enough oxygen-rich blood to help Lily grow, run or play like other four-year-olds. Her doctors performed two more open-heart surgeries, and Lily and her mother spent the better part of two years living in the hospital as the girl clung to life. At each phase, the family wondered if Lily would be strong enough to survive the next surgery or even the next day.

Congenital heart disease is the most common birth defect in children, so the team at Children’s knows typical patterns and expected outcomes for most of the children it sees. In Lily’s weakened state, with just one lung and extensive scar tissue from her previous surgeries, she would be an extremely risky transplant. Doctors across the region declined three times to place her on the heart transplant list, reminding Emily that donated organs are rare. She recalled them saying: “‘we need to make sure that the recipient of these organs is as healthy as possible so that this donation can actually make a difference in a life.”

Dr. Janet Scheel had recently been hired to rebuild the center for Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplant at Children’s, so she felt particularly cautious.

“At first I told the family she might be too high-risk to do there at Children’s. Then of course her personality made me relent and take the risk and I’m glad I did,” she said.

Early on June 14, 2014, Lily’s transplant began, and her new heart was in place less than 12 hours later.

Long before the transplant, playing with her sisters often ended with Lily blue-lipped and struggling to breathe. After, she was breathing with one lung and on oxygen. Her muscles had atrophied over months in the hospital, so she traveled to and from physical therapy in a stroller. Though weak, she remained hopeful. When she saw posters promoting the Race for Every Child, they inspired her.

“Any time anybody would ask her, ‘What are you going to do when you’re out of the hospital?’ she would always tell them, ‘When I’m better and I’m out of the hospital, I’m going to run,’” her mother remembers.

It became her mantra: I want to run.

Farther Than That

“Why do we call it your hero’s heart?” Emily asked Lily.

“Because it’s a hero?” Lily tried.

“Because a hero gave it to you,” Emily reminded her, and Lily nodded solemnly.

The Rancourts don’t know much about their donor yet. There was a car crash and the victim’s lungs could not be donated, so Lily received their heart and pulmonary arteries. Doctors had hoped to restore blood flow to her right lung but were unsuccessful. The family does know that the surgery was difficult — it lasted most of the day and Lily went into cardiac arrest several times.

Recovery was no easier. Lily took 26 medications per day under the watch of a nurse. Doctors thought she might need her supplemental oxygen tank for the rest of her life. Her healthy heart struggled to adjust to her single lung and she remained frail and vulnerable.

At this point, stressed and exhausted, Emily started running. Her own mother began running marathons at age 60 and encouraged her daughter to try it as a form of self-care. In those quiet moments, Emily found her own love of running, and when she came home, she could expect Lily and her nurse to be cheering her on from the driveway.

With Lily still ailing, Emily began to wonder if the girl would ever be able to run and play. Lily’s medical team encouraged Emily to start Lily off like any beginner — see how far she could go, and the next time, try to go just a little farther.

So Emily brought Lily’s portable oxygen tank outside and the two ran to the next house on their street, a distance of about 200 feet. Within a few days, Lily was running a few houses, and then Emily was bringing a stroller along so that Lily could take breaks as they ran longer and longer distances.

About a year after the transplant, at a follow-up appointment, Lowell Frank, a runner and one of Lily’s cardiologists in her long history with Children’s, suggested that she run the 100-yard dash at the Race for Every Child. Emily remembers Lily asking how far that was. When Dr. Frank showed her, the girl was unimpressed.

“I can run way farther than that,” she told him.

“In hindsight, that was probably a big insult, huh?” said Frank, laughing as he heard the story. With the approval of Scheel, they agreed that Lily should try the 5k distance. In October of 2015, Lily donned a Supergirl costume and lined up with just her mother, after bad weather rescheduled the race. Emily carried her oxygen tank and pushed a stroller so the girl could take breaks. Just 15 months after her transplant, Lily finished the race by running into Dr. Frank’s arms for a hug.

By 2016, Lily needed neither the oxygen nor the stroller to complete the race, which is fortunate because Lily’s brother Thaddaeus has been undergoing procedures for his own open-heart surgeries and, potentially, his own heart transplant, and he rode alongside his sisters. When he’s ready, Lily is keen to help coach Thad in his recovery and running. But she’s going to start with her mother, who is nervous to jump from the 10-mile distance to a half-marathon.

“I have to teach her!” Lily gushes. “I’ll get a whistle and I’ll blow it and then she will have to run! Around the cones! Until I say stop, I say stop and I blow the whistle.”

Then she’ll help Thad in his recovery, because she remembers her own sadness at not being able to play. Then she’ll coach her sister Mackenzie hardest of all, making her do “jumping laps.”

“It’s like a jumping jack run all around the cones and it’s going to get harder and harder for her. And she’s gonna think, ‘I can’t do it!’” said Lily, who, as you can see, doesn’t exactly traffic in self-doubt.

Princess on the Run

On a snowy Saturday morning, Emily and I asked Lily how running makes her feel.

“Happy!” she cried, leaning towards me and grinning from ear to ear with the checkerboard smile of a child well-known to the Tooth Fairy.

She added, “It makes me have a lot of energy.” When she runs, she can feel her heart beating in her chest and feel grateful that she’s no longer in the hospital.

“We always said that Lily looks like Snow White,” Emily said. “We put a red bow in her hair and she looks like Snow White. And so we have a lot of pictures of her in the hospital in her little red bow.”

Lily has more in common with Snow White than the fair skin and black bob. She is warm, generous and giggles infectiously. In the Disney film, Snow White’s jealous stepmother orders a hunter to kill the girl and cut out her heart; unlike Snow White, Lily’s heart surgery was wanted and ended happily. Lily plans to dress as Disney’s version of the princess for the 2017 Race for Every Child but she prefers the Snow White depicted in her favorite book, Princesses on the Run by Smiljana Coh.

Lily started clapping excitedly as she described the book. In the story, princesses run away from their castles to escape the idleness of royal life. When they return home, they change their habits to become happier. Rapunzel gets a bob so she can exercise comfortably, Lily remembered. “Sleeping Beauty was doing yoga and Snow White was still running.”

“Snow White was pretty much the one convincing everyone to keep running. She never stopped,” Emily explained. “We said, that’s just like Lily! She was always encouraging her sisters to keep running during the race and just like Snow White, who never stopped running.”

The Girl on the Posters

A new heart can transform a child’s life, and Lily’s doctors want their patients to have full, unlimited childhoods after these difficult procedures.

“Patients like Lily, who were born with congenital heart disease … often haven’t been as active simply because they don’t have the stamina,” Scheel said. The parents, she said, become accustomed to having a sick child, “and I come along and say, ‘Okay, they can go to school. They can go to gym.’ They look at me like I’m crazy.” But according to Frank, very few heart transplant recipients need to restrict their activities afterwards.

“I’m typically optimistic and I counsel parents all the time that, you know, your kid’s a normal kid, they could be a normal kid. Seeing Lily able to do that is really gratifying,” he said.

At the hospital, Lily used to see posters promoting the Race for Every Child and dream of running. Now, she’s the one on the posters, beaming with every inch of her being, superhero logo on her chest, cape billowing behind her. Another child, perhaps sleeping in Lily’s old bed, can draw strength from this girl who has been through so much.

This story was originally published in the Spring 2017 issue of RunWashington

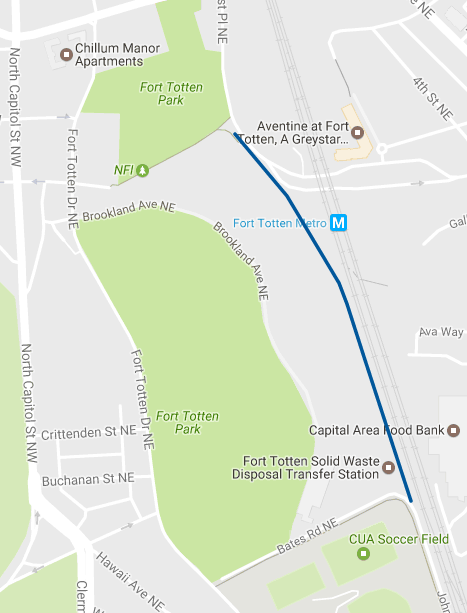

Runners in the District can expect more miles of trails in the city in the next few years, as the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) prepares for the next phase of construction on the Metropolitan Branch Trail in northeast D.C. DDOT is seeking contractors to build the next off-road portion of the trail, from John McCormack Drive, near Catholic University in Brookland, to the Fort Totten Metro station in Upper Northeast D.C. Once that contractor is identified and work begins, they estimate the construction will be complete in 18 months. If the process goes smoothly, DDOT hopes to award the contract by Summer 2017.

Until this point, the route through this section of the trail has been largely on uneven, narrow sidewalks, past the pungent Fort Totten waste transfer station and up a steep incline. While runners may enjoy the hill training, bicyclists have long cited safety concerns on this stretch, as the sidewalks are not suited for riding and the grade of the hill makes it difficult to maintain a safe speed in the road.

“We are hoping that cyclists, pedestrians and runners embrace the convenience of this trail,” said DDOT’s Michelle Phipps–Evans. “Even though it is only about half a mile, it closes a critical gap and avoids the steep hill on Fort Totten Drive, where there is no trail and cyclists are forced into the street.”

The new trail segment will have LED lighting and security cameras, features that DDOT plans to add to the existing trail as well. LED lights are expected this year, with cameras to follow. They tout new signage as raising awareness of the trail in the fast-changing neighborhoods that border it. The trail has occasionally been the site of high-profile violent crimes. However, community groups have hosted events to draw more users to the trail, hoping that more eyes would improve everyone’s overall safety and enjoyment of the route. These events have included movie nights, a Bike to Work Day pit stop and a 5k to draw users to the trail.

“More users generally mean more safety in numbers — for riders, walkers and runners,” Phipps notes.

In a post detailing the plans for the extension, the Washington Area Bicyclist Association noted that the work will be the first major construction on the trail since the existing southern section of the trail opened in 2010.

Once completed, the Metropolitan Branch Trail will provide a route from Union Station to the Silver Spring Metro station, over eight miles of sidewalk, cycletrack and trail through many of the city’s residential neighborhoods. These follow the extension of the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail completed last year, which provides an off-road route from southeast D.C. to College Park.

Tensions run high in the D.C. region these days. The recent political transition has created uncertainty for federal workers and brought thousands of protesters into the streets, and all this lands on top of deepest winter and the other everyday stresses we all endure. Amid all this, one group of runners recently ran random acts of kindness through the city at the DC Capital Striders’ Random Acts of Kindness Run.

Heather Rosso, 46, of Reston, inspired and led the event, which featured a route planned by DCCS President Rick Amernick. On Jan. 26, Rosso and nine friends met to run a three-mile route through the Shaw and Bloomingdale neighborhoods of D.C. Along the way, they handed out more than 60 gifts–candy, toiletry packs, hats, gloves and even just kind words–to the people they encountered. Some they left out for passersby to find.

“I don’t count them because, to me, it’s not about the gifts per se,” she said. “It’s about the kindness behind the gifts.” She wants to connect people with kind gestures, and the objects serve as an icebreaker above all.

Rosso began randomly enacting kindness a few years ago on her birthday in keeping with her Buddhist faith. It was also part of a long recovery she made over eight years, after an injury led to an undiagnosed spinal infection, which in turn led to years of pain and a battle with depression. When she finally began to recover, she felt called to give something to others.

“To a degree, it’s a very noble but very simple goal, so it’s very achievable,” Rosso said. “The basis is spread more kindness. Even if you do that for just one person, you’ve actually accomplished the goal. I think it always ends up being exponentially greater than we think [for participants].”

In past years, Rosso and a smaller group of friends would give out gifts that she purchased near her home in Reston. “I have a knack for finding odd deals,” she admits. She has netted discounted winter gear before, and last year, she bought 45 flowers to hand out for her 45th birthday. This year, friends also gave money to buy gifts and gathered at her home to help pack them.

Rosso is a longtime trail runner and member of DCCS and the Virginia Happy Trails Running Club, but it took Amernick’s encouragement for her to bring the two together. Her generosity came from her own pain and celebration, so the event was deeply personal. In addition, kindness is a small moment between people, and she is reluctant to lose that intimacy. But she was inviting her running friends anyway so they pushed forward.

“Running makes it visible,” she realized as the night went on. The group, the speed and the spandex drew attention to what they were doing and allowed the runners to reach more people. That’s what she wants more than anything. Rosso envisions the RAK Run spreading to other clubs across the region and reaching people in more neighborhoods–kindness going viral, as she puts it. But for now she’s content to keep it to close friends and a birthday celebration. And people on the receiving end are still surprised by the gesture.

“People are just so unused to people just being kind for the sake of being kind,” Rosso said. “To see that, it’s sort of heartwarming and heart wrenching at the same time.”

For her, this is as much a reason as any to perform more kind gestures for the people she meets. But you do have to get past that initial awkwardness of approaching and interrupting strangers. Rosso laughs brightly at their attempts.

“I’m not trying to sell you something, I’m not trying to convert you, I’m not trying to make you join a cult, I’m not trying to make you do this,” she laughs. “We had to preface it with ‘We’re on a mission to spread more kindness.’”

You probably know an ultrarunner, and not just the ones you read about in Born to Run. The sport has grown significantly in recent years as more marathoners ask what’s beyond 26.2 miles. In D.C., ultrarunners hide in plain sight, working for the government, opening donut shops, or practicing law. They infiltrate your road marathons, casually enjoying a bagel while you’re trying to stomach another gel. They’re your colleagues, your neighbors, your friends. And if you’ve been thinking about taking on these more extreme distances and conditions, they’re your best resource for getting into the sport.

The ultra club

With some 635 members, 20 events, and three major races per year, the Virginia Happy Trails Running Club is the hub of ultrarunning in the D.C. region.

“We’ve been here right from the start, sort of being a driving force to have events and runs that appeal to everybody,” said club president Alan Gowan.

The club has grown in the last few years as younger runners join the sport, and the club has adjusted to fit members’ interests. That includes partnering with the D.C. Capital Striders on a weekly trail run in Great Falls Park.

Striders President Rick Amernick has come to admire ultrarunners’ tendency to mentor one another.

“A lot of [Striders] (who) had never thought of doing an ultramarathon caught the bug because you’re running with people that sign up for these races, 50k, 50 miles, even 100 miles,” he said. “Some of our runners have completed those races over the last several years strictly because they were encouraged by the runners who they saw on a regular basis [who] said, ‘Hey, why don’t we train together?’”

Lauren Masterson, president of the Washington Running Club, came out to Great Falls while training for her first 50 miler this year. She turned to ultrarunning as a way to stress less about her road marathon times, but she still felt timid before her first run.

“All these people are gonna be so hardcore and they’re gonna be jumping off rocks and just blazing through these trails,” she remembered worrying. “And a lot of them are,” she added, “but they are so welcoming. They have this great Facebook page where people post questions and you’ll get like 10 responses and it’s just been so informative.”

“It’s a real close-knit group,” agreed Tom Corris, a 15-year VHTRC member, “and it’s cliche to say that we’re all family but yeah, we’re pretty damn close to it.”

More cowbell, please

In April, at the finish line of VHTRC’s Bull Run Run 50-mile race, runners rounded the final turn, greeted by the clatter of a cowbell. Kids toddled alongside their fathers to the finish, where race director Alisa Springman greeted them with a high five, handshake, or hug. Volunteers tugged perforated timing stubs off of race bibs and handed out t-shirts. Two-liter bottles of soda lined a picnic table in the finisher’s chute, but the good grub was up a hill in the Chow Hall, where members of VHTRC dished out chili, brewed coffee and shot the breeze.

“You don’t want to disappoint anyone,” said Springman, who has run the race herself 10 times but was directing it for the first time with her husband. “You know what your experience has been like as a runner and it seems seamless, so you want to provide that for the same reasons, so other runners experience that.”

For 350 runners, she recruited a team of 150 volunteers to support the race in rain and even an unseasonal burst of snow.

Like many others, she called the community “tight-knit” and “family.” In a race like the Bull Run Run, she relies on volunteers to make the event run smoothly, but she also relies on the runners to watch out for one another. “You don’t have to spend weeks and months and days and years with a person on the trail to get to know them very well,” she noted. “Oftentimes, an hour or two on the trail where you’re really open and connected to things emotionally, you share a lot more and you feel much more connected than you would otherwise.” This isn’t just talk for her, either; Springman and her husband met at a trail race. “It took off from there!” she said.

The D.C. Scene

Most people don’t think of major urban areas when they imagine trail or ultrarunning, but the D.C. region does not lack for training routes. In Rock Creek Park, more than 30 miles of paved and unpaved trails wind between commercial and residential neighborhoods of Northwest D.C. Great Falls has another 15 miles in Virginia, and across the river, the C&O Canal Towpath runs past miles of detours on its way to Cumberland. In a relatively short drive, you can reach the Shenandoah or Massanutten mountains, Harper’s Ferry or parts of Pennsylvania.

“You would never know that there’s opportunity for trail running here,” said Larry Huffman, who found VHTRC in early 2010 and ran a 50k within the year. Huffman lives in Tyson’s Corner, the rapidly urbanizing suburb just two miles from Great Falls. He runs to the Wednesday night workouts.

Although our mountains are a bit less majestic than the west coast’s, decorated marathoner and ultrarunner Michael Wardian sees a lot of upsides to living here.

“It’s not ideal to live in a major metropolitan area if you want to be really successful (running) in the mountains,” he said. “But it’s possible. You just have to work a little harder.”

Wardian has been known to train with his treadmill at its maximum incline to prepare for races out west, although he regrets that he can’t mimic the brutal descents that follow those climbs.

Like many of us, he stays here to be close to friends and family and the D.C. food scene. When he travels for races, which he does often, he can choose from three airports and virtually every carrier, making his trips more flexible and cost-effective. His friends in Montana don’t have that luxury.

“I feel like it’s worth that kind of tradeoff to be able to get all the perks that we have living in a place like this,” he said.

Wardian has raced around the world and has seen a lot of terrain, but he settled pretty quickly on the destination most like home: Costa Rica, where in 2014, he won the 225k Coastal Challenge Expedition race through the rainforest.

“The climbs aren’t super big and the trails are super duper similar to the U.S. […] That was really neat. I felt really comfortable on those trails,” he said. Most notably, the climate is “kind of like our summer heat. It’s like soupy, hot, humid, which is great for me but a lot of other people from different climates like the Northwest or West Coast kind of suffered. That was something that made me feel at home.” Endlessly optimistic, Wardian has found an upside to some of the worst traits of D.C.’s weather.

VHTRC member Josh Howe of Chantilly gushed about the Instagram photos of a friend who recently moved to Colorado, but he has no plans to leave just yet.

“It may be expensive to live here,” he said. “Traffic may suck awfully bad, but we have some pretty awesome trails around here. Within an hour you can be in the mountains.”

The ultra effect

Even if an ultramarathon doesn’t spark your sense of adventure, ultrarunners generally agree that thinking or training like them can make a difference at shorter distances thanks to the improved endurance, nutrition habits and mental toughness that come from their training regimens.

“You can use that speed that you get in a 5k, 10k, half-marathons, marathons to be able to have a quicker turnover and be a more efficient runner in [ultramarathons],” said Wardian, who turns up for shorter races around the city when he’s in town. “Then you can use that strength and power and discipline that you have from doing the longer stuff to be even that much of a stronger, more competent runner in shorter stuff. I think there’s a nice balance.”

Ultrarunners also develop an ability to eat real food on the run and a highly articulated sense of their nutritional needs. When Josh Lasky started training for his first ultra, he would buy a Chipotle burrito and try to eat it during the workout. “Bit by bit, bite by bite,” he said, “you take that burrito down.” With his stomach acclimated, he can sustain himself on slow-burning whole foods for most of his races, then get a boost from sugar and caffeine to power him to the finish.

“Nutrition is paramount in getting through these things,” Masterson said, who trains mostly on nutritional drinks but likes to grab some potato chips and soda during races. “I’ve seen grilled cheese,” she said of the aid stations, “They have little sandwiches, salted potatoes, french fries; it’s like a junk food fest and it’s awesome.”

If you do decide to take it on, ultrarunning can shake up everything you know about yourself as a runner. “Whatever you run on the roads really doesn’t matter,” Masterson said. Between technical skills, extreme conditions, and the sheer duration of the event, ultrarunning requires a totally new approach to training and racing. You cannot go fast and gut it out. Your GPS probably won’t work; even if it does, your mile splits will be at the whim of the next hill. Your supplies will disappear, your headlamp will die, or your feet will blister; something will go wrong despite your best planning. You will feel soaring highs and profound lows and you will learn to eat when you start crying. If you’re capable, you will keep going, pushing on to find out what physical or emotional boundary you can crack next. This is not a sport people do for fun in the moment; if anything, they do it to feel the pain, to endure it, and to find out who they are on the other side of it.

“[Ultrarunning] brings you to a place of resourcefulness and being uncomfortable in a way that you’re not in your normal, everyday life, where you’re very pampered and everything is accessible and problems are relatively mild and quickly solved,” Springman said. “So a little existential, but there’s something kind of primitive about that, I think, to just get back to something more basic, where the only thing you have to focus on is moving forward and all the other noise and distraction is gone.”

Lasky has a philosophical take that he’s mulled over the course of many miles. “I think the reason why ultrarunners do what they do is because they don’t have the ability to imagine it and they’re not satisfied with the imagination alone…” he said. “It requires a willingness to come face to face with your own mortality, your own limitations, your own strength.” Lasky took up the sport after several years caring for his disabled father as well as a lengthy recovery from a broken ankle. For him, ultrarunning is a test of his limitations and a display of gratitude for his own mobility.

“You’re gonna be in your head a lot,” Amernick said, “I feel like crap, I can’t believe I’m doing this.” He recalls his first 50-mile race last year; at mile 40, he blurted out to a volunteer, “Why do people do this?!” At the finish line, he announced, “I’m never going to do this again!”

Within a few hours, he was asking, “When’s the next one?”

“And that’s what happens,” he said. “That’s what happens. This experience has basically embraced you. You don’t realize it at the time but maybe a day later, a week later, you can look back and go:

“Oh my god, that was amazing.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2016/2017 issue of RunWashington

The Marine Corps Marathon brings thousands of spectators to Washington D.C. and Arlington every October, all of whom just want to see their runner and enjoy their time in the nation’s capital. In 2014, we published a spectator’s guide of advice from our editor. This year, we asked local runners and their friends for their best advice to making the most out of that morning. Use this guide while developing your plan for the day to best support your runner and make the most of your morning!

Get Around

Running & Walking – John Pickett of Alexandria attempted Marine Corps twice in the mid-80s, but estimates he’s spectated 10-15 times since then. “The MCM is great for spectators because the course folds back on itself,” he notes. “You can get two views of the runners relatively easy at Capitol Hill and in East Potomac Park, for example. And you can go from the start to the midpoint in a mile or two instead of 13 miles. It’s next to impossible to do this with a car or transit when a marathon is not going on. It’s worse with the race going on, of course.”

Bicycling & Capital Bikeshare – Pickett, however, is more in favor of bicycling to get around the course. “Bikes are much better [than walking] because they are faster and you can carry stuff (like your favorite runner’s discarded jacket),” he writes. He outlines a detailed spectating plan that rides past a half-dozen points on the course, detours for coffee and apple fritters, and still gets you to the finish to see your runner “in their death throes,” as he puts it. “Better them than you, right? Try this on foot and you’ll give up at the cafe on the Hill.”

If you don’t have your own bike, Capital Bikeshare is an affordable alternative to get you around that morning. It costs $8 for a daily membership, which offers unlimited 30-minute rides (fees apply after that) and docks available across the course. You can purchase single rides for $2 (fees apply after 30 minutes). Check CapitalBikeshare.com for pricing information, service disruptions, and other updates.

Metro – Metro is your best transit option if anyone in your party has limited mobility, but it has several drawbacks. It’s usually extremely crowded. This year, the system is in the middle of massive safety overhauls, so Metro will not open early on race day. According to the Washington Post, eight-car trains will run after 7 a.m. on the blue and yellow lines, with some expanded service during regular operating hours. If you do choose to use the transit system, make sure to purchase a SmarTrip card ahead of time and add enough money to get you through the day.

Driving – Not recommended! Check out the Spectator Shuttles being offered by race organizers to get you from parking areas to the course.

Get your Caffeine Fix

Between the early alarm, brisk autumn air and four-ish hours of movement, a coffee drinker is bound to need a pick-me-up. And while you can usually find a Starbucks, DC has a blossoming coffee scene that’s worth checking out. Samantha, a DC-based runner and coffee lover who blogs at A Brewed Awakening, has run MCM once and spectated once so far. We asked for her favorite coffee spots near the course.

Arlington

Bayou Bakery (1515 N. Courthouse Road, Arlington)

“The best coffee you can get here is an Iced Nola. It’s made with chicory coffee from New Orleans, which is a dark, smoky style coffee, half-and-half, and simple syrup. It sounds unimpressive, but it really is delicious. The one big problem here is, it’s usually freezing at the beginning of the race! So if you want to try the Iced Nola, make sure to bring some gloves to keep your hands warm.”

Georgetown

Baked and Wired (1052 Thomas Jefferson Street NW, Washington, DC) or Georgetown Cupcake (3301 M Street NW, Washington, DC)

“Almost every local will tell you to go to Baked & Wired for superior cupcakes and I know I am in the minority when I say I think Georgetown Cupcake is amazing. Either way, you can’t go wrong, though Baked & Wired does have a way better coffee selection.”

National Mall

A coffee desert, unless you have time or a bicycle to get you to a nearby neighborhood. Samantha suggests, “if you do have an hour or so to spare before seeing your runner one last time before they head over the bridge back to Arlington, take the metro to Chinatown and grab a cup of coffee at either Chinatown Coffee Company or La Colombe.”

Crystal City

Commonwealth Joe (520 12th Street S, Arlington)

A newly opened shop between Crystal City and Pentagon City. “I’ve never been here, but after looking at a map in the area to see what’s there I found Commonwealth Joe, and it looks amazing!”

Go to the bathroom

Runners usually line up dozens deep at the port-o-potties along the course, but you should leave those race amenities to the runners and find another option. If you won’t pass your hotel or home, the Lincoln Memorial and Washington Monument have public restrooms. Be prepared to wait in line.

Get a great photo

Cheryl Young can be spotted with her camera at most regional races, taking photos and cheering for her teammates with Capital Area Runners. We asked her for the best places to snap a memorable photo of your marathoner. In exchange for sharing these secrets, she asks spectators to remember not to step in front of the professional photographers on the course. “Go behind them so you both get a great shot of your friend. Yes, your iPhone pics are awesome, but….”

Key Bridge (Mile 4.5)

“This is my favorite spot by far. It’s mile 4.5ish- early in the race- and everyone is still pumped and happy! Plus, you can stand on the concrete barricade and get a nice bird’s-eye view to pick out your friends.”

Kennedy Center (Mile 8.5)

“It gets congested, so make sure you are in a spot where you have a long line of sight of the runners as they come towards you (if are on a curve, you won’t have as long to look for them – they’re coming faster than you think!)”

Lincoln Memorial (Mile 14.5)

“This is another of my favorite spots. Lots of time to look for them (as long as you are far enough down with a good line of sight).”

Last Mile

“Mile 26 is going to be crazy, so keep walking towards mile 25 until the crowds are less and you can find your friend. This is where your friend will need for you to give them every bit of your energy, so turn on the cheers, and I don’t care what they look like, you tell them they look GREAT – SO STRONG!”

Support the Runners

Runners appreciate the support of enthusiastic spectators, so come prepared to cheer, clap and make a ruckus. For the advanced spectator, “One of the best things is when [spectators] have salty snacks or Kleenex or something like that in the later half of the race when you really need a pick-me-up,” says Tammy Whyte, a three-time finisher. She remembers pretzels and chips in Crystal City last year, “and it was greatly appreciated.”

Definitely don’t…

Yell “You’re almost there!” “unless you are standing at mile 26 and the runners only have .2 left to go,” says Jess Milcetich, an MCM finisher and five-time spectator.

Get too edgy with your signs. “Good spectators cheer for everyone and do not make triggering signs,” says Megan McCarty, who was troubled by a sign at the Baltimore Marathon that made light of a presidential candidate’s recently unearthed remarks about sexual assault. Everyone is tired of this election, so find a more uplifting angle.

Dart in front of runners. “If you do have to cross [the course], be mindful of the runners – the best way is to run with them and diagonally run toward the other side. There is almost nothing worse for the marathon runners than to have a spectator jump in front of them and cause them to lose their groove,” Young says.

Definitely do!

Make a sign!

“Funny signs and young kids doing high fives is also great,” Whyte says.

McCarty agrees, asking for “positive and interactive” signs. In Baltimore, she saw a little boy with a sign that said “Tap this for a boost!” and a picture of a mushroom from the Mario games.

Download the tracking app!

“Having the ability to know where your runner is at certain points in the race is really helpful to gauge how soon they might get to where you are waiting for them,” Milcetich says. “Plus sometimes races can be crowded and you might wonder if you’ve missed seeing your runner at a certain point, the apps usually let you check pretty quickly to get a sense if that is that case.”

Have fun!

Your friends and loved ones have worked for months to get to this point, so bring your best mindset and biggest smiles. You woke up early and trekked miles because you care about this runner. Enjoy it!