This article originally appeared in the January/February 2014 issue of RunWashington.

Runners run, elected officials legislate and besides the dozens of honorary congressional chairs for the Cherry Blossom Ten Mile, never the twain shall meet.

Until October 2013. The first federal government shutdown in 17 years threw the running community into uncertainty as runners were ostensibly banned from National Park Service property and race permits for that land disintegrated, putting the region’s marquee race in doubt.

On one hand, despite signs warning that parks were closed, runners flocked to the C&O Canal Towpath, Rock Creek Park and the National Mall. Beach Drive, normally closed on weekends and holidays, was a free-for all. Parks Service Police officers cruised past runners in East Potomac Park who dodged the gate past Buckeye Drive with nothing more than a polite wave, though after a few days a patrol car sat at the intersection.

During the shutdown, the parks service issued 97 warnings to people to encourage them to leave closed park lands, and one citation was issued to a jogger in the greater Washington area- in Turkey Run Park Oct. 2, according to NPS Acting Chief Spokesman Jeffrey Olson.

“The mission of the National (Parks) Service is twofold — to protect the resources of the parks and provide for their enjoyment by the American people,” Olson said. “With no, or extremely curtailed, staff on hand due to the lapse in appropriations, we would be unable to adequately protect the park resources, nor the people who came to attend such events.”

Furloughed workers found themselves, with the relief of knowing they’d eventually get back pay, able to train like the pros. Hit some doubles, take a nap, make use of free time for strength training.

But anyone signed up for some of the region’s big races, though, was left wondering just how long the shutdown would last and if it would affect their schedules.

They found out quickly. On Oct. 2, Steve Nearman postponed the Woodrow Wilson Bridge Half Marathon, scheduled for four days later. Why? Eight miles of the race traveled the George Washington Memorial Parkway, a NPS-maintained road.

“I had to balance giving (budget) talks a chance, because I didn’t want to make a decision too early and wind up being able to hold the race,” he said. “If there’s anything I’ve learned from friends in the business who dealt with the New York and Boston marathons this year, you don’t want to wait too long (to communicate), so I decided that we’d give people a little time to change their weekend plans.”

His race moved to Nov. 10, one of the few weekends Nearman could work around the various police departments that come together to make the race possible. The rescheduling likely cost him half the field.

“It’s a shame, because Nov. 10 was a beautiful day,” he said. “The make-up date ended up being on the back side of a lot of marathons — Marine Corps, New York — and just a week before Richmond, so that took it off of a lot of people’s calendars.”

Nearman started worrying around Labor Day that the race could be affected by a government shutdown.

“It was a short month for Congress to get its (budget) resolution together and the Syrian (chemical weapons) situation took attention from that,” he said. “I knew it wasn’t going to end well, but you have to live in hope things can be worked out.”

Supply vendors cut him a break and let him move his rental back five weeks.

“They knew the postponement wasn’t because we weren’t prepared or committed to the event,” Nearman said.

Other races had to adapt, too. Oct. 13’s Boo! Run for Life 10k ended up becoming a 5k and sharing a course with the Run to Remember. Runners scheduled for three legs of the Ragnar Relay starting in Cumberland, Md. and following the C&O Canal Towpath for some time found themselves running with teammates on later segments. The Mount Vernon Trail race moved to Mount Vernon District Park from Fort Hunt Park. The Run! Geek! Run! 8k rescheduled to mid- November and races, like the Stokes School 5k and Take a Sick Day Run a 5k, were cancelled outright.

The Monster Mask 5k, scheduled for Oct. 13, went on as planned on the C&O Canal Towpath. Race director Elizabeth McClure contacted the National Parks Service for clarification and received no response.

“We parked everyone off site, we had them walk to the start and finish line and did a thorough job cleaning up,” she said. “There were other runners outside of our race on the towpath.”

Nevie Brooks blogged about the race, “We engaged in full-on civil disobedience, running along the C&O Canal on National Park Property. The whole event was kept pretty quiet… And save for the national anthem played quietly, no pump-up music.”

The big one

As the days wore on and the debate over the congressional impasse sputtered, the calendar drew closer and closer to Oct. 27. The Marine Corps Marathon. As one of the most popular marathons in the country, it attracts tens of thousands of runners and spectators, making in an annual economic presence. In 2010, the race attracted nearly 69,000 people from outside of the Washington area, who spent $38 million in connection with the trip, according to a study by the George Washington University International Institute of Tourism Studies. That generated more than $2.7 million in tax revenue for state and local governments.

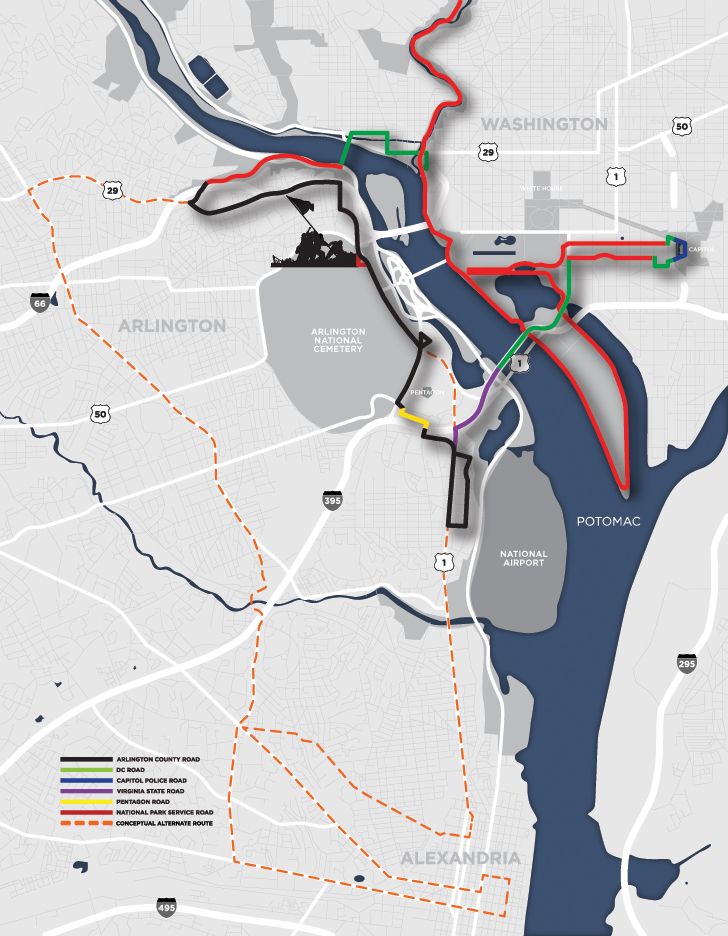

All of that was in jeopardy because 15 miles of the course was on NPS roads, with another three on D.C. roads. The George Washington Memorial Parkway – roughly 1.5 miles. Rock Creek Parkway, East Potomac Park and the National Mall– 13.5 miles. More than half of the course would be unusable.

“This was probably more of a challenge than any other race because you were removed from the influence of fixing the problem,” said race director Rick Nealis. “In years past, it’s been construction, or a problem with the permit, or even running past a crime scene after 9/11, but every year there’s someone you can reach out to and try to influence the decision process. Not this year.”

The race staff was fine, all paid with nonappropriated funding, but even before the government closed Oct. 1, there was some pressure. Contract specialists had already been affected by sequestration furloughs. It was one-day-a-week for the most part, Nealis said, but the backlog was going from annoying to worrisome.

“A one-day delay isn’t as serious, but once you start getting close to October, you don’t have the luxury to lose a day because there aren’t that many days left,” Nealis said.

The meaning of the government shutdown took a while to sink in.

“We didn’t really understand the scope of the National Parks coming to a complete close,” Nealis said of Oct. 1. “None of that was shared even from their standpoint– what does closure even mean? There was some word that some monuments would be left open.”

A day later, the Wilson Bridge Half announcement cleared it up, the canary in the coal mine.

“I think that was the eye opener,” Nealis said. “They were cancelling permits and they’re not going to be allowing us to do certain things. It sunk in, going to the Marine Corps War Memorial and seeing the barricade blocking the Iwo Jima statue.”

Now what?

While his staff worked, as full-steam ahead as possible, Nealis looked at the options. The situation could be resolved any time, so the team had to be ready.

Setting an alternate date for the race, already close to the end of fall marathon season, wasn’t an option. Too many out-of-towners composed the field.

What about a different race course? The race’s date complicated things.

Though Congress controls the District of Columbia’s budget until this coming January, the city had a surplus that would keep local services operating until Oct. 17. But the marathon was 10 days later.

“If you had a non-park property event in D.C. those first 17 days, chances are you were alright,” Nealis said. “If this was the (Rock ‘n’ Roll USA) marathon, we might have been able to pull it off, D.C. was basically working.”

If there was to be a second route, it would be restricted to Virginia.

“We reached out to Arlington County to see if they had 18 miles where we could run a marathon,” Nealis said. “What we heard back wasn’t encouraging.”

There was nowhere to go that would not be a disappointment for the runners and a headache for residents. The most reasonable alternate route followed the first few miles of the course and continued to Glebe Road, then down to Alexandria and back.

“You look at the course and realize, ‘That’s a nice course you got, but didn’t we just encircle this whole neighborhood? Do you have any idea how many churches are in there? And hospitals?'” Nealis said. “We’d have to win the hearts and minds of our runners. But the running community’s not going to be happy, they’re going to want to see the (Marine Corps War Memorial) statue. ‘I ran this race to see Washington D.C., not Glebe Road.'”

So, on an intellectual level, it was looking like a loser.

“Even after we pull this off, they’re not going to appreciate that they just had some rotten course we made them run through,” Nealis said.

Practically, the fallback course became exponentially more complicated as it went on.

The limited number of police officers worked on the long stretches of Rock Creek Parkway, which has few intersections and needs only light staffing. Taking the course through heavily populated parts of Arlington County and Alexandria would require much more manpower.

Officers from neighboring jurisdictions were already spoken for, supporting Arlington County

officers working on the race. Nealis also refused to cut security staffing on the course, which in this case would have meant reducing staffing levels the race dictated for traffic control. Wooden barricades alone wouldn’t suffice.

Traveling up Route 1 though Crystal City, blocking access to Ronald Reagan National Airport, was also a non-starter.

“When you look at the map of the area, it looks like there are plenty of options, Nealis said. “But you look closely and realize ‘oh, that’s the GW Parkway’ and all of a sudden a second course is a lot harder.”

Another possibility, running in the HOV lane on I-66, was shot down almost immediately. So was a series of laps around the Pentagon. But those possibilities were considered.

“We really wanted to make this race happen,” Nealis said. “Nobody wanted to have to cancel.”

With miles of open roads in Prince William County, Va., the race could be run at the U.S. Marine Corps Base Quantico, 36 miles south of the marathon start line. But that would involve bussing runners back and forth, leaving many spectators out and straining to reach the course.

“New York busses its runners, but just one way,” Nealis said.

The race management team was sure from the beginning if they pulled off the race with an alternate course, it would not be certified.

“We’d call up the Boston Athletic Association and see about getting an exception for people who’d hit the mark here,” Nealis said.

Cancellation station

So cancellation became the most likely option if Congress didn’t agree to a deal. Two weeks before the race, the parks service kept Verizon from installing a data line to the finish area. That served as a practical reminder that time was running out and eventually milestones were passing, making catchup much harder.

The Marine Corps hierarchy gave Nealis until Oct. 18 to make a decision, yes or no.

“We knew we didn’t want to be another New York Marathon,” he said. “Once we made a decision, we were going to stick with it. If we cancelled and they opened up the parks the next Tuesday, sure people would Monday Morning Quarterback it.”

“Legal review of the registration (agreement) said ‘no refunds,’ but we wanted to give people a refund- at least 50 percent maybe 100,” Nealis said. “But from a runner’s standpoint, they don’t want a partial refund or a full refund, they want to run.”

And when would they run? With a registration lottery due to debut in 2014, guaranteeing spots to 2013 registrants would drastically cut the number of new registrants.

At roughly $100 per entry, refunding most of 30,000 entries would cost the race $3 million.

More than $1 million was going toward law enforcement, which as a simple line item could take the race’s losses down to less than $2 million. Deliveries of supplies hadn’t arrived. Could they be cancelled?

“Our contract people, the legal representatives of the government, were furloughed,” Nealis said. “Rick Nealis can’t pick up the phone and say, ‘stop the banana shipment.’ Somebody’s either got to make the contracting guy essential and have him come to work or every contract we had was going to be deliverable and we’d have to pay for it.”

Among the floating legal issues: what cancellation would mean for sponsorships that help defray the cost of holding a massive race.

Word gets out

While Nealis and his staff adjusted with a steadily shrinking calendar, a few days before the deadline, the restless public got frantic when a news report justified their fears. On Oct. 15, Arlington County news website ARLnow reported that the Army 10 Miler, which used part of Rock Creek Parkway and was scheduled for Oct. 20, would be rerouted. Lt. Dave Green, of the Arlington County Police Department Special Operations Section, elaborated about the marathon.

“I don’t want to put people in panic mode, but if as of Friday evening the government is still closed, it’s probably not going to happen,” ARLnow quoted him as saying. It was a big scoop for ARLnow editor Scott Brodbeck (profiled in November/ December 2013’s RunWashington), who was motivated even more to find out because he was registered to run the marathon.

The mark on the calendar was now public.

“That was probably the best thing that could have happened,” Nealis said. “It forced us to confront the issue. We had just been treading water about when to announce our plans.”

Marketing and communication staffers had been dealing with a steady line of questions about the race, answering that the race would go on, without details to prove it. At that point, they were going on faith that the race would happen, the government reopened and everything back to normal.

“The immediacy of social media made this a challenge,” said Marc Goldman, the race’s marketing director. “In years past, you could put out an announcement and you might get a few phone calls, but now you get dozens of questions and comments a minute on Facebook. Since it was a situation we weren’t in control of, we had to focus on being decisive. We looked a lot to New York in 2012 and knew being on-again-off-again in regards to cancellation wouldn’t work. The fallout would be less that it was cancelled and more about uncertainty.”

Nearman agrees on the importance of social media.

“I wish I had someone watching it all day, turning the tide with openness,” he said. “If you can’t stop the bleeding, you’re going to get slaughtered, because social media can be like a gun to your head. The important thing is that you can’t make decisions to placate people on Facebook.”

Those people on Facebook were angry. Accusations flew that race organizers were misleading runners, but most understood the federal government situation’s was to blame. Many wrote encouraging the race committee. Hundreds made declarations that people would gather to run the route anyway on Oct. 27 at 7:55 a.m. Some came with offers of help.

Matthew Reimer of Jacksonville owns a small race timing business and offered to bring his equipment with him and time a replacement race.

“I was half joking, but the truth is there were so many people on Facebook willing to contribute that we could have pulled something off,” he said. “Maybe not the same route, but somewhere in the city. Maybe loops around the Mall.”

Most advocates for a potluck race expressed confidence that the authorities couldn’t possibly stop all of the runners who would mob the streets.

What Reimer was serious about was making something of the marathon season this year. In 2012, he and his wife deferred their Marine Corps spots so they could run New York. As they were walking to their gate at the Jacksonville airport, they saw the alert that they race had been cancelled. They left the airport, hopped in the car and drove north, looking for a race. They found the Rock ‘n’ Roll Savannah Marathon two-and-a-half hours away and next day ran a race Reimer described as “awful.”

“When the news came out that the Marine Corps race could be cancelled, our first thoughts were, ‘Not again,'” he said. “We were about a day away from pulling the plug on the race and just taking the trip to sightsee when it was back on.”

Others expressed regret that a cancellation would disappoint many first-time runners whose triumphs would be denied, or at least deferred. Twinsburg, Ohio resident Tricia Cusma had four friends training with her for Marine Corps, one because she wanted to run a marathon after turning 40. They trained every week on the Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail in Cuyahoga National Park. After the government closed, runners continued to use the trail, until reports of

$100 citations scared them away. Loss of the park and trail impacted the Towpath Marathon, scheduled for Oct. 12, which was pushed back to Nov. 2. It got Cusma and her friends nervous.

“We supported each other through it,” she said. “The first-timers, especially, needed some encouragement. We were also going to lose what we put into airline tickets, hotel rooms, all of those things that go with taking a trip.”

“There was also the point that Marine Corps is what we planned to do,” she said. “If it came to that, we could stay home and run the Towpath Marathon a week later, but it was a backup plan.”

For runners outside of the Washington area who didn’t see government employees every day, the shutdown was starting manifesting itself in their lives.

What’s the matter with Utah?

Eleven days into the shutdown, the state of Utah paid to open five national parks and four national monuments in an effort to save the already-damaged tourist season. That deal paid roughly $167,000 per day to open those parks.

Could that work for the Marine Corps Marathon? Even if opening the GW Parkway, Rock Creek Parkway, and the Marine Corps War Memorial cost as much as Arches, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion national parks, split among the 30,000 registered runners, the cost would come out to less than $6. A more realistic estimate, given the difference in size and staffing between the parks in the Washington area and Utah, would have been much less.

The problem, however, was political.

“Utah had a governor willing to step up and take the lead,” Nealis said. “We didn’t have the governor of Virginia or the mayor of D.C. championing our race. Their names weren’t on it; It wasn’t the Virginia Marathon or the D.C. Marathon.”

The proximity to the problem also undermined that plan.

“You can get away with opening a park in the west, but if you’re talking about opening up the grass in front of the Capitol — the center of all of this — you lose political muscle and populist appeal,” Nealis said. “We approached Virginia’s congressional delegation but didn’t get a good feeling about it.

“If we just had to open up the (Iwo Jima) memorial, that might have had a chance.”

But there was no ace in the hole, congressional rescue. Just as in running, there was no short cut. Work had to be done to get results and it was entirely up to Congress.

“We are so on” – Rick Nealis

Most, if not all of the contingency planning, the worrying, and the frustrations evaporated when a budget compromise was announced late Oct. 16 and approved Oct. 17.

Out of the process came the sense that there was no backup for the Marine Corps Marathon. It exists as a relatively inexpensive race in an expensive city that draws massive crowds because of what more people now realize is a careful balance. There are long, meandering parkways that are great for running and require less traffic control than in almost any other city, but if conditions aren’t right in the legislature, they could be gone.

In marathoning, a good day might just be holding steady, finishing in one piece, let alone setting a PR. In marathon management, the same might be said for getting the race off – superlatives like course records and finisher number high-water marks becoming secondary.

The Cherry Blossom race is entirely on NPS land. When the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, two weeks before the race, word was that if the terrorism threat level was high enough, the parks service could rescind permits.

“We started looking at other places to have the race, mainly in Montgomery County,” said race director Phil Stewart. “Losing permits is a hazard any time you’re on federal property and in D.C. that’s a lot of places.”

Stewart also directs the Race for Every Child 5k at Freedom Plaza, which was held on Oct. 5 and had to adjust because of the shutdown.

“Freedom Plaza itself is NPS, so we had to move the staging area onto Pennsylvania Avenue, which is D.C.,” he said.

Stewart saw the 2012 cancellation of the New York Marathon as changing runners’ attitudes, demonstrating that no race was sacred.

“That really sent the message to the running community, any race can be cancelled,” he said. “I think runners are more accepting of that risk – weather, terrorism-related, its’ a societal thing.”

It’s a different change from the 1970s, when New York Marathon founder Fred Lebow said the race would always go on.

“There was definitely a macho feeling back then, but the races were not nearly so interwoven with municipalities,” Stewart said, noting that Lebow probably made that declaration before New York became the five-borough race it is today. “Races want to use higher profile real estate in cities and that makes things more complicated.”

Success story

Where Marine Corps faced a growing list of problems as organizers considered alternate courses but had a few weeks’ cushion, up the Potomac River in Shepherdstown, W.Va., Mark Cucuzzella was able to pull off a save.

The fifth-year Freedom’s Run Marathon was due to start Oct. 12 in Harpers Ferry and follow the C&O Canal Towpath to the Antietam Battlefield, both of which would be unusable, on the way to Shepherdstown. Eighteen miles, out of bounds.

“I started looking at alternatives the week before the shutdown,” said Cucuzzella, the race director. “The parks [service] made it clear it was a no-go, so that made it an easy decision.”

Cucuzzella had an idea. His favorite running route – River Road – outside of Shepherdstown. As far as shutting down long stretches of road went, it didn’t inconvenience too many residents. It was close to the finish area, which also doubled as the start for the half marathon, 10k, 5k and kids’ race. Most importantly, it was far removed from any closed national park land.

“It wasn’t a course I’d want to use every year – a lot of people come to run in the parks,” he said. “But I got the sense people were so pissed at the government situation, you could sense they were going to show up to spite it all.”

The race ended up boasting 358 marathon finishers and 656 half marathon finishers, more than its 2012 totals.

Reorganizing the course on the fly, compressing two months of preparatory work into two weeks, renewed Cucuzzella’s faith in people.

“There was a Norfolk-Southern rail line I was worried about having to cross,” he said. “Turns out a dispatcher showed up (unannounced) and offered to manage the trains’ logistics so they wouldn’t interrupt the race.”

Like Nealis down the river, Cucuzzella learned the most disruptive possibility wasn’t even a consideration before this year.

“You plan for all your contingencies, but this isn’t one I put on the radar,” he said. “I feel fortunate we were able to pull it off without anyone saying they felt like it was a waste.”

Recent Stories

Looking for our race calendar? Click here Submit races here or shop local for running gear

Zebra Dazzle 5k Walk/Run or 100 Bike over 30 Days

Join the Zebras for this Zebra Dazzle event for all fitness levels. The 5k Walk/Run has 2 options. You can participate as an onsite participant on 9/13 at Carter Barron in Rock Creek Park, NW Washington DC or as a

Hero Dogs 5K9

Hero Dogs Inc will host its 5th Annual 5K9 race at the Congressional Cemetery on Saturday, May 17th, beginning at 8 am. There will also be a 1K Fun Run. The 1K Fun Run will start at 8 am sharp