This year’s Marine Corps Marathon may be just like previous years’ races. And that’s just fine with Race Director Rick Nealis.

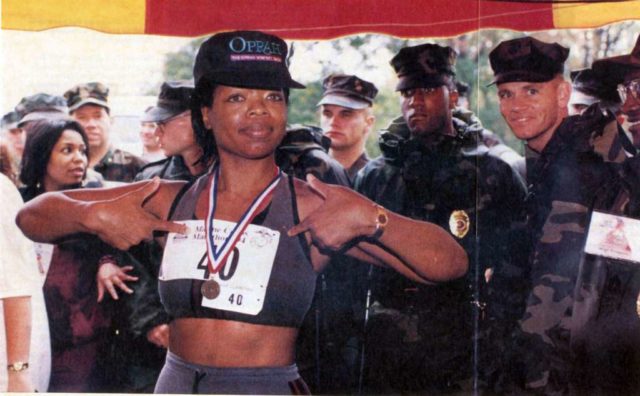

He’s seen a lot during the quarter century he has led the October race: cheating, celebrity runners (namely, Oprah), security concerns and even a scandal in which runners were urinating dangerously close to Arlington National Cemetery graves. Now in his 26th year leading “The People’s Marathon,” things “surprisingly … look like the status quo,” he said.

But he is always prepared for a debacle that could impact the marathon through D.C. and Arlington. It has happened many times on his watch, and chatting with the loquacious 64-year-old is a like revisiting some of the area’s most memorable moments over the past two-and-a-half decades.

“As a race director 26 years ago, I worried about if the bananas were yellow [because] if the bananas were green, the runners weren’t going to eat them,” Nealis said. “Each year it gets a little bit more sophisticated. Whether you’re putting 5 or 6 ounces of water in a cup and if the bananas are yellow – those are far down on my list now.”

Race direction has evolved, as has the marathon’s complexity as a major event. He first took on the position as an assignment when he was a Marine.

Nealis’ first year as race director in 1993 was what he called a “wake up call.” That year, the marathon was embroiled in a cheating scandal after the winner Dominique Bariod of Morez, France, was found to have cut tangents in the course. Of course, the runners behind Bariod followed suit, calling the leaders’ times and placement into question.

“That year the Washington Post’s headline read ‘The few, the proud, the cheaters,'” Nealis recalled.

That same year, reporters noticed white male runners were urinating near Arlington National Cemetery – Section 27, to be specific. The section inters thousands of African Americans: about 1,500 of the first black combat soldiers of the Civil War and almost 3,800 former slaves. Needless to say, the action brought scrutiny from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Nealis said.

“After that first year, I though ‘OK if I can survive this race, I’ve learned a couple of things,” he chuckled.

There were years the race has run smoothly and years it has been more of a task. In 2000, the race was briefly denied permits because “there were too many flags.” The next year, 9/11 happened. It jeopardized the race, but Nealis encouraged participants to keep training, show up and run the race – without knowing if the course that went right by the Pentagon would be approved.

About five days before the marathon, the FBI lifted restrictions near the Pentagon making it possible for runners to pass the building where just a few weeks earlier American Airlines Flight 77 struck the landmark, killing 125 people in the building as well as the flight’s passengers and crew.

“There was so much pulling at us and I knew … I don’t think I knew enough to be scared,” Nealis said of the post-9/11 race. “The people who came in 9/11 – I applaud them even more because there was so many unknowns. And as a runner it’s so easy to stay home and say ‘it’s not safe.’ But they came, and those who ran that year, it was probably a highlight of their running career.”

Things didn’t get much easier the following year when the D.C. sniper had the region on edge. The threat of the sniper canceled many local events, including Halloween, Nealis recalled, yet he remembered thinking: “If we could do it after 9/11, we could surely do it again.”

Luckily, the snipers – John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo – were captured and arrested about 72 hours before the marathon. Nealis said the arrests “made my life a little bit easier” because the deadly, high-profile attacks could discourage participants from coming or worse, put them in serious danger.

His most challenging year at the helm? It was the 2016 race when Metro’s major trackwork closed stations and limited hours, Nealis said. The rail system didn’t open early as it usually does for the race, forcing Nealis and his team “to really get creative.”

Over the several years, wars, hurricanes and major D.C. events siphoned the marathon’s support staff, imperiled the race course or threatened reserved parking lots for runners, but somehow Nealis said the marathon always happened.

“You think a race is going to be just a 26.2 mile race. People come and people go, but there’s always something to put a different twist on each year’s race,” he said.

This year, Nealis had his eye on the military parade that President Donald Trump advocated for. The parade, which has since been canceled, was set for Veterans Day and had Nealis worried that it could take some of the military resources he relied on for the marathon.

As fall approaches, federal budget concerns, major weather events and mass casualty events around the world are always on the mind of this race director. When Nealis sees more recent events such as the 2018 Las Vegas shooting and 2017 Charlottesville riots play out, he thinks about how he can adapt to make the marathon a safer event.

“We are always trying to anticipate the unknown… Before last year I didn’t know how many hotels or high rises were along the course, but now I do,” Nealis said of the shootings in Las Vegas where a gunman killed 58 people from a high-rise hotel room.

Nealis is always adapting for the future of the race, but knows at the core of the Marine Corps Marathon is a group of people dedicated to accomplishing a goal and doing so strategically. In turn, Nealis has turned marathon running into a more palatable pursuit and the race into a “bucket list” life event, said Alex Hetherington, a member of the race’s Hall of Fame who has known Nealis for more than 20 years.

“He recognized the potential of the race and as a Marine and someone who loved the Marine Corps. He has made himself into one of the premiere race directors of any stripe,” said Hetherington, who joined the Marines in 1985. “He has this idea of running a marathon for something that’s greater than just running. It’s about honor and an opportunity to run for a purpose that’s greater than oneself.”

Also, Nealis’ passion for the marathon is infectious, Hetherington said, which translates to the event.

“Rick sort of spins like a top when he’s talking about the marathon,” Heatherington said. “That’s his gift – he gets people excited about the event and all it encompasses.”

As Nealis looks ahead, he knows the Marines will always put on a stellar event that leaves a lasting mark on participants: “People always remember a Marine putting a medal on them,” he said.

Still there is some concern for the future of racing. The price to run marathons (in the case of the Marine Corps Marathon, $175), can deter some runners from ever getting into the hobby, Nealis said. The average marathon cost is $60-$100, the Road Runners Club of America wrote in a 2012 article. Arguably, the prices have only increased since then.

As events get more expensive, races like The People’s Marathon may not be embracing a large part of the population who would like to participate due to financial constraints, Nealis said. And while he doesn’t have an answer for cost-cutting methods, he worries about the next generation of runners who may never lace up their running shoes.

Nealis, now ever-nearing traditional retirement age, said he doesn’t see leaving his race director job any time soon. He admits hanging around Marines makes him feel young, and runners’ positivity and ambition keep him motivated. He said he is living the dream.

“Being a race director, you get to stand on the finish line a lot and you get to see the faces of the runners – and you know you are touching lives.”

Recent Stories

Looking for our race calendar? Click here Submit races here or shop local for running gear

Zebra Dazzle 5k Walk/Run or 100 Bike over 30 Days

Join the Zebras for this Zebra Dazzle event for all fitness levels. The 5k Walk/Run has 2 options. You can participate as an onsite participant on 9/13 at Carter Barron in Rock Creek Park, NW Washington DC or as a

Hero Dogs 5K9

Hero Dogs Inc will host its 5th Annual 5K9 race at the Congressional Cemetery on Saturday, May 17th, beginning at 8 am. There will also be a 1K Fun Run. The 1K Fun Run will start at 8 am sharp